- Home

- Heidi Squier Kraft

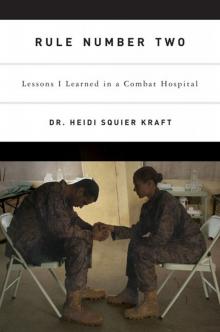

Rule Number Two

Rule Number Two Read online

Copyright © 2007 by Heidi Squier Kraft

All rights reserved. Except as permitted under the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Little, Brown and Company

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue

New York, NY 10017

Visit our Web site at www.HachetteBookGroup.com.

The Little, Brown and Company name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

First eBook Edition: October 2007

ISBN: 978-0-316-02297-2

Contents

Copyright

Author's Note

Foreword

Preface

The Beginning, Part I

Alpha Surgical

Fever

HOME

Damn the Rockets

HOME

The Legend of the Camel Spider, Part I

The Eye in the Sky

Karen’s Boots

HOME

Dunham

Combat Action Ribbon

Convoy

The Irishman and the Lightbulb

Fallen Angel

HOME

Hero, Part I

HOME

Cheeseburgers, Part I

Light Discipline

Friday Night Fights

HOME

Up the Stairs

HOME

One Good Eye

HOME

Rule Number Two

The House of God

Mr. Oda

Reality

The Best We Could

HOME

Hero, Part II

HOME

The Optimists

HOME

Godspeed, Marines

HOME

One Hawkeye

Woman’s Best Friend

HOME

The Legend of the Camel Spider, Part II

The Little Boy

HOME

The Last Patient

Cheeseburgers, Part II

Drowning

HOME

The List

The Beginning, Part II

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

About the author

For Deb Dunham,

the mother of a hero

And for Mike “Cheez” Kraft,

my hero, then and now

This book is dedicated to the people of Alpha Surgical Company, especially Karen Lovecchio, Bill Reynolds, Cat Kesler, Steve Noakes, Katie Foster Saybolt, Jesse Patacsil, and Dextro Gob . . . from whom I learned the meaning of the word comrade;

to the United States Marines whose care was entrusted to us in Iraq;

and to Jason Bennett, the finest doctor I have ever known, my partner in the desert, and my friend forever.

Author’s Note

The people, places, and events described in this book are based on my recollection of them, to the best of my memory’s ability.

With the exception of Corporal Jason Dunham, the name — and all identifying characteristics — of every patient described in this book has been changed.

Foreword

An incredibly intense and special bond exists between Marines and the Navy medical personnel who serve with us. The medical officers and corpsmen, our beloved docs, are not graduates of Marine boot camp or combat training. They are medical professionals with brief orientations — a whole eight days — to the operational environment. The Marines protect them like the royalty they are. They handle everything from preventive medicine, routine sick call, and dental care to emergency response and surgery. They bind our physical wounds and just as surely salve our mental casualties. They share our risks and revel in our successes. They weep with us, often for us, over our losses.

This is the story of one deployment of one medical officer — a mother and the wife of a Marine — who also happened to be a Navy psychologist. She was deployed to Iraq to care for the Marines and the medical personnel.

It is a very personal story, but it is also the story of all the men and women of the Navy and the Marine Corps in Al Anbar province in Iraq. Behind the newscasts and the headlines lie the real lives of the warrior class of America, many now on their third or fourth tour in Iraq. Rule Number Two is the story of the strong men and women who are doing the nation’s bidding so that others may pursue their lives undisturbed.

W. C. Gregson

Lieutenant General (Retired)

United States Marine Corps

Preface

September 2006

My dear Brian and Megan,

You were fifteen months old. You don’t remember.

On an isolated air base in Iraq, somewhere between the Sunni triangle and the Syrian border, a small group of U.S. Navy doctors, nurses, and hospital corpsmen attempted to stabilize the trauma of war. They ducked their heads and ran to the helicopters that landed in their hospital’s backyard. They unloaded wounded U.S. Marines, put them on stretchers, and carried them to waiting triage teams. They battled, day after day, the same grief and fear they saw in the eyes of their patients.

A tiny team among these Sailors — made up of a psychiatrist, a clinical psychologist, and two psychiatric technicians — provided mental health care for over ten thousand Marines in western Iraq. For nearly eight months, these four people fought to keep their patients, and one another, functional. They found themselves leading trauma interventions that were different from anything they had ever studied. It quickly became evident that combat mental health was anything but an exact science, and they strove to provide individual moments of comfort amid the chaos. They worked alongside their patients to uncover those wounds that surgeons would never see.

I was the psychologist on that team.

Your daddy, who flew attack jets in the Marine Corps for eleven years, gave me a card the day I left for Iraq. In that card, he wrote that he was proud of me for taking care of the men and women of the greatest fighting force in history. I packed my bags, and we all said good-bye.

I left your daddy there — with the generous help of your grandparents, who left their home and their lives to come and live with you — to take care of you, my children, so I could go halfway around the world to take care of someone else’s.

I returned home just before your second birthday. It was the most difficult thing I have ever experienced, trying to reconnect with a Marine husband who had faced the unique challenge of staying back while his wife went to war and with children who had truly grown up while I was gone. One day, I started writing about those eight months away from you. Originally, I thought I would want to forget my time in Iraq. It turns out I was wrong.

I wanted to remember the pride of serving with the most extraordinary people I have ever known, so I would always treasure those friendships. I wanted to remember the grief of watching young men die and the anguish of telling their friends of their loss so I would never again take the gift of life for granted. Most of all, I wanted to remember the courage and the character of the Marines whose care was entrusted to me, so their sacrifice would be known to as many as I could tell.

Above all, I wanted to share those things with you.

Some of the memories I’ve included here for you are very sad, as they tell tales of great loss. War is traumatic, and that trauma is illustrated in some of these pages. While I was in Iraq, I learned firsthand about the cost of combat. And about the price of freedom.

I wrote this book so that the sacrifices of the Marines who fought in Iraq, and of the Sailors who took care of those Marines, would be remembered.

And I wrote it with the

hope that you will both be able to understand, at last, why I had to go.

I will always love you.

Mommy

The Beginning,

Part I

Pagers have come a long way. When I was an intern ten years ago, our beepers produced a horrible, shrill sound — unsuitable for the human ear and audible to anyone who happened to be within a half-mile radius. By January of 2004, when I served as a staff clinical psychologist at Naval Hospital Jacksonville, my pager seemed downright polite, its muted singsong alert barely perceptible across the room.

Even that benign tune, however, sounded harsh and annoying in the middle of the night — exponentially so if I was on vacation.

My mom and dad had traveled from California to spend postholiday quality time in Florida with their fourteen-month-old twin grandchildren. I took five days off — in truth, largely to spend an entire week watching my parents watch my children.

One night during their visit, the peal of my pager awakened me at 0300. I staggered to the kitchen, splashed water on my face, turned on all the lights, and dialed the number displayed on the beeper. The resident in the emergency room told me about one of my patients, a very young Sailor who was about to become a very young single mother. At twenty-two weeks pregnant, she had experienced dangerous preterm labor, and as a precaution she had been admitted to a civilian hospital that would be able to care for a premature baby.

As the resident’s voice rambled on, I sank into a chair at the kitchen table and lowered my forehead to my palm. I was always striving to separate the feelings of a clinician, who made decisions rationally and calmly, from those of a woman and mother, who sometimes did not. This became more challenging at 0300. Inhaling deeply, I closed my eyes and counted to five, slowing my heart rate before exhaling. With a sense of renewed control, I decided to visit my patient in the hospital the next morning, and I returned to bed.

Four hours later, I woke out of fitful, anxious dreams about my babies with the sense that I could not ease their pain. Pain about what, I could not remember.

The obstetricians controlled my patient’s labor, and her baby remained safely in her womb. Relieved, I left the hospital midmorning, arriving on base in time for a farewell luncheon for our department head, Captain Goldberg. The four psychologists in the department, who had become one another’s trusted friends both in and out of the hospital, looked to the captain as a protector and role model. We would miss him terribly.

At lunch, Captain Goldberg talked about how the new conflict in Iraq might affect us. He had been with the Marines when they had pressed to Baghdad less than a year earlier. Home for seven months now, he still seemed far away sometimes.

“I pray that this war will not place any of you in harm’s way and away from your families,” he said, making eye contact with each of us. “There is no indication this will occur in the near future — but if the unexpected happens, I have faith in all of you, as psychologists and officers.”

As we filed out after lunch, each of us stopped to say a personal good-bye.

“If I am called, sir,” I told him quietly, “I will do my best to make you proud of me.”

I drove home along the river. Feeling connected with God as I gazed at the sun sparkling on the water, I said a prayer for the men and women of this war. I thought of my father and his service in the Navy during both the Korea and Vietnam conflicts, about which he never spoke. I wondered if our Operation Iraqi Freedom veterans would come home to a different world.

I almost didn’t hear the singsong tune of my pager over U2’s “Sunday Bloody Sunday,” which I always turn up too loud.

“You’ve got to be kidding me,” I mumbled to myself, rolling my eyes at the sight of our department phone number on the display. I picked up my cell phone and dialed.

“Heidi?” Our new department head, a lieutenant commander psychiatrist, answered the phone directly. “I was the one who paged you.”

“Hi, Elissa. What’s up?”

“Are you driving?”

“Yes.”

“You should probably pull over.”

“Elissa, what’s going on? Is everyone okay?”

“Everyone’s fine. But you should pull over.”

“Okay, okay.” I found a place to park along the riverfront road, under an ancient Florida shade tree whose leaves had been taken by winter. The afternoon sun already felt like spring.

I turned off the ignition and waited, my heart thumping audibly. She cleared her throat.

“Okay, I’m just going to say it. I got a call from the front office today. You have eleven days to report to Pendleton. Apparently, the West Coast psychologist who was supposed to deploy with First FSSG* has been pulled to do a float on a helicopter carrier. You’re going in his place.”

I sat in silence.

“Heidi?”

“I’m here.”

I pulled into my garage with no recollection of the drive home. I sat motionless, staring at the dashboard for a few long minutes, and then I forced my muscles to move, gathered my things, and opened the door.

My mother and Meg, holding hands, emerged in the hall. My baby girl smiled when she saw me, her huge green eyes bright. I could hear my dad’s animated voice as he read to Brian in another room. I crouched down, and Megan let go of her grandma to teeter across the ceramic tile into my outstretched arms. She circled my neck with tiny, warm hands.

“Ma-ma-ma-ma.”

I held Megan tightly, tears flooding my eyes and spilling down my face. Looking over her shoulder, I met my mom’s concerned eyes.

“Oh, no,” she breathed. “Did something bad happen to your patient’s baby?”

“No,” I whispered, kissing the top of Meg’s bald head. I shook my head and inhaled deeply.

“They’re sending me to Iraq.”

Alpha Surgical

I was not the only medical person who had been plucked from a stateside hospital to join the people of Alpha Surgical Company at Marine Corps Base Camp Pendleton as they prepared to deploy. In fact, only a handful of the personnel were actually organic to the overall medical battalion in peacetime; the majority of us were pulled from major Navy medical facilities to augment the mobile field hospitals.

I was, however, one of only two people who arrived at Camp Pendleton that first day, to find that Alpha Surgical Company had already left for Iraq.

Captain Sladek, a hematologist/oncologist in his twilight tour before retirement, and I had both been given erroneous reporting dates by our parent commands.

Upon the discovery that our unit was gone, the two of us were informed that we would prepare for deployment and travel into the theater with the personnel of our sister company, Bravo Surgical, which would be based at Fallujah. Once we arrived in Kuwait, we would be transported to Iraq to meet up with the company to which we actually belonged.

The captain and I began the transition process together, enduring countless questions from everyone we encountered regarding why our names were not on the lists they had in front of them at the moment. We sat in the back, stood off to the side, and giggled at the fact that since no one knew we were there, no one would know if we disappeared. And yet there we stayed.

And there we sat, together on metal bleachers with Bravo Surgical, on the first of eight deployment training days at Marine Corps Base Camp Pendleton.

We were eighty Navy medical people — surgeons, physicians, psychologists, anesthesia providers, dentists, podiatrists, nurses, and hospital corpsmen, most of whom were based out of either Naval Medical Center San Diego or Naval Hospital Camp Pendleton. For the majority of us, this was our first experience preparing for combat operations of any kind, and we felt awkward and hesitant in the company of thousands of intense Marines.

In the week that followed, together we hauled empty seabags to fifteen different warehouses on base, methodically filling them to their brims with heavy combat gear. Together we donned gas masks and practiced in the gas chamber. Together we learned how to dism

ount a vehicle if a convoy was attacked and how to assist the Marines in the protection of that convoy. Most of us managed to deny we would need that one.

Together we were issued 9mm pistols and thirty rounds of ammunition.

At the end of the eight days, everyone wept or whispered good-byes to their family members who had come before the sun rose to see them get on the bus. Everyone, that is, except Captain Sladek and me, whose families were across the country. I carried a farewell card from Mike, my Marine officer husband, in my cargo pocket. He wrote that he and my twins would be fine. He told me there were people who needed me more than they did right now.

So I stepped onto that bus with eighty people who swiped at tears and waved through the windows to their children. I put on my sunglasses, although it was still dark, and leaned my head back on the seat.

Several long and cold February flights later, we arrived at a base in Kuwait, a huge staging area for troops entering and exiting Iraq. For a little less than a week, close to a hundred females crammed into one tent, tucked our seabags under the cots that were lined up wall to wall, and attempted to find a way to pass the time.

It was during this week that I met Sandy, a pediatric surgeon with Bravo who had a two-year-old daughter. We became inseparable, talking about our children, our husbands, and our apprehension about what might lie ahead of us in Iraq. Several female Marine officers with cots nearby felt sorry for Sandy and me, I think, and they helped us learn to quickly clean and check our weapons. We washed our socks and underwear in the sinks in portable shower trailers since word to ship out could arrive at any moment and there was no time to use the laundry service. It was dark and very cold, and the wind howled at the canvas of the tent as we slept.

No one slept very well.

And then one day, when Sandy and I returned from breakfast, a Navy Chief met us at the entrance to our tent.

“Lieutenant Commander Kraft?”

“Yes.” I hadn’t met her before.

“I’m Chief Edmonson with Alpha Surgical. We’ve been waiting to get the remaining members of the company together before we make our push into country. We’ve got everyone now.” She grinned at me.

Rule Number Two

Rule Number Two