- Home

- Heidi Squier Kraft

Rule Number Two Page 3

Rule Number Two Read online

Page 3

“I don’t have my flak and Kevlar here,” I said. My voice sounded small, unfamiliar, and distant.

Crack. Jason stuffed his ammunition in his cargo pocket. “Come on, I’ll go with you to get it.”

In the dark, boots thumped through passageways, fists pounded on doors, and voices shouted orders. Officers and senior enlisted men huddled together at the front hatch, talking excitedly. Jason and I moved through them.

The female barracks was one hundred yards away, a straight shot over uneven dirt and rocks. We waited. A full minute passed without an explosion. Jason grabbed my elbow and led me down the stairs.

We ran.

Like the men’s building, the passageways of my barracks building were darkened. Jason held out the blue squeeze flashlight that hung from his dog tags and illuminated the combination lock on my door. My fingers quivered so fiercely I was afraid I wouldn’t be able to turn the dial. I did, but missed the right numbers. I used every psychological trick in the book to slow my breathing. I found it nearly impossible to practice what I preached.

I got it on the second try. We opened my door and I slid into my flak vest and fastened the chinstrap of my helmet. “Let’s go,” Jason said, motioning to the group of people who were already running across the field to the hospital.

As I closed the door and replaced the lock, Karen, a junior nurse officer, appeared in the passageway. She was a petite woman, just over five feet tall, but she looked even smaller in her big vest and imposing helmet. Her brown eyes were huge and frightened. I suddenly felt brave. I grabbed her hand.

Jason led the way and the three of us sprinted across the field. I clutched Karen’s hand the whole way. Our breathing raced under the adrenaline rush and the thirty pounds of extra weight. We ducked into the front entrance of the hospital, gasping. Our company commander stood in the lobby area and barked for everyone to go to condition one. This weapon configuration, with a magazine inserted and a round in the chamber, had been the one I honestly thought I would never actually use.

I looked at Jason in disbelief. He shrugged, pulled the slide of his pistol back, and chambered a round. Karen and I did the same.

From outside in the cool desert night came the distinct thumping of multiple attack helicopters taking off and turning outbound over the hospital.

They were rockets. They had been fired toward our base from miles away, and when they struck the dirt and burst into razor-sharp fragments, the resulting crack was astoundingly loud. The rockets also made a bizarre whizzing sound just before contact with the ground, but it took us some time to learn to recognize that. Our deployment changed at the first moment of impact. We became vulnerable in a way that few Americans will ever understand.

By 0330, all incoming casualties had been treated and all medevacs* had departed for Baghdad with our injured patients.

We considered ourselves very fortunate that we hadn’t accidentally shot our own comrades that night. It was the first and last time weapons in condition one were allowed inside the hospital.

We were told to return to our barracks and attempt to get some sleep.

The idea of sleep was a joke. I lay wide awake on my cot, too paranoid to permit myself to blink. I listened to the distant shouting of men’s voices and the occasional popping of gunfire. Several times during the night, the anxiety overwhelmed me. I got up and knocked on the door next to mine in the barracks, behind which my psychologist colleague and friend Jen was also wide awake. The two of us sat, arms wrapped around each other, shivering, for what seemed like an hour but may have been ten minutes.

My heart rate remained elevated, my hands remained frigid, and my eyes remained open during those three cold hours until sunrise. And my thoughts raced. I thought about people in our world who had lived through the horror of being bombed. For the first time in my life, I had a real sense of empathy for them.

I saw a detached image of my own death, even allowing my mind to wander to a mental picture of the car driving up to my house in Florida, and two uniformed officers stepping out. When the vision became too clear, I gulped, squeezed my eyes shut, and forced it away.

I imagined my children and found that, although I could picture them in my mind, I experienced genuine difficulty feeling them. I fought to retrieve those tactile memories. After many long moments of searching, I sensed the actual warmth of Meg’s tiny body, her little bald head resting on my shoulder. I felt her baby skin smooth against my fingertips. I grew increasingly panic-stricken, however, when a similar sensation of Brian eluded me. I lay completely still and focused on breathing. I battled every external distraction, silencing the sounds of the night and the pounding of my own heart by sheer will, until at last a memory emerged.

The night before I had left for Iraq, Brian suffered a fever and a cough that racked his little body and kept him awake. I had retrieved the coughing baby from his crib and carried him to the couch in the family room. Lying on my back, I rested him on my chest and placed a blanket over both of us. He fell asleep, his face turned sideways over my heart, and the rhythm of his labored breathing synchronized with mine. I stayed awake that entire night watching him.

Tears of relief flooded my eyes. And I knew at that instant I would be unable to function in Iraq if my children stayed at the forefront of my consciousness on a day like today.

In a world where rockets exploded randomly nearby, I decided I could not be a combat psychologist and a mother at the same time. I had to be one or the other.

I had no choice. I put their pictures away.

HOME

My friend Nisha is a redhead, like me. She is also a clinical psychologist in my department in Florida and the mother of a boy and a girl. And she had deployed to Iraq with the Marines when Captain Goldberg did, in 2003. While our experiences in country turned out to be very different, her words were always a comfort.

An e-mail from her waited for me one morning, one among a large in-box of supportive notes from friends and family. She included updates on our friends and her family, as well as good hospital gossip. Her last paragraph caught me off guard:

I know this is the most difficult thing you’ve ever done. I also know a part of you is dying inside, as the days of your children’s lives go on without you. I remember the feeling. Fight that. Keep that part of you alive. Listen to the music that feeds your soul. Write in your journal about your grief. Most important of all, find another mom and take turns crying to each other.

I thought of Sandy, the pediatric surgeon whose cot had been next to mine in our tent in Kuwait. Her daughter had just turned two, and although we barely knew each other, we felt immediately connected. We even bought matching stuffed tan camels for our babies and had their names embroidered in Arabic and English at the tailor shop on base.

Then I had come to Alpha Surgical while Sandy went to Bravo, in Fallujah. We had known each other six days. It felt like six years. Leaving her was horrible, and Nisha’s e-mail made me realize why.

The people there with me were terrific. Even this early in the deployment, I knew that a handful of them would be some of my most trusted friends for the rest of my life. But the way I would survive would be different from Nisha’s.

I did not have another mom out here with whom I could take turns crying.

The Legend of the Camel Spider,

Part I

Since the first day a member of the U.S. military set foot on Middle Eastern sand, the tall tales of the giant prehistoric arachnids who lived there, camouflaged by that same sand, had grown to the size of the spiders themselves. (This was rumored to be roughly equivalent to the diameter of a dessert plate.) But they were not just huge, legend said. These desert monsters sprinted — at ten miles per hour — and had a vertical leap of four feet. And by the time Alpha Surgical Company set up shop in western Iraq, they also had two rows of razor-sharp teeth and growled like rabid wolves before attacking their helpless human prey.

We had been in the hospital less than a month when our first crit

ter casualty appeared. He was a Navy SEAL, a hulk of a man with icy eyes. He was admitted to our medicine ward with a high fever and a nasty cellulitis that spread up and down from the bite on his arm. Before admitting defeat, however, he had captured his nemesis alive.

It was not a camel spider. It was a scorpion. He proudly delivered it to his doctor in an ammo can. Dr. Sladek, our senior medical officer, took one look at the intimidating creature and promptly called the Bug Guy.

The Bug Guy, a Navy entomologist from the preventive medicine unit in country, arrived soon after receiving word about our special warfare Sailor with the sting that was not responding to typical scorpion treatment. The Bug Guy looked into the ammo can and with the giddy excitement of a small child announced, “That’s a death stalker!”

Fortunately, he also knew how to treat the sting of the death stalker. After telling the medical staff what to do for the ailing SEAL, he delivered an impromptu Bugs and Snakes lecture for the rest of us.

The eyes of the group of doctors, nurses, and corpsmen who stood around him widened in horror as we heard about what we were up against. It was worse than we thought.

One to 2 percent of the invisible sand flies, the culprits behind the three-week-long episode of excruciating itchy bites that we seemed to suffer every day, carried a serious skin disease called leishmaniasis, the Bug Guy explained.

“The good news,” he expanded, “is that they are quite bad at flying, so running a fan at night will keep them grounded.”

He also told us that the huge mosquitoes that emerged from our shower drains and swamp cooler vents — impervious to our military-issue repellent — did not carry malaria. This was a good thing, as we had not been issued anti-malaria medication.

He warned us about the cobras, who hid most of the time but were vicious if cornered, and about the scorpions, the most dangerous of which had stung our SEAL after taking shelter in his sleeping bag.

“Neurotoxic venom,” he said. “It’s a good thing your patient is as big as he is and that he came in when he did. It could have been a lot worse.”

Finally, the Bug Guy described the infamous camel spider, which none of us had yet seen and none of us wanted to see. He explained that, while they were large (the size of a human hand, not a dessert plate) and fast (probably closer to five miles an hour than ten), they could not actually jump very high. He added that they like the shade, and have been known to run alongside a person to stay in his shadow. We looked at each other incredulously, picturing this image, which could not have been more terrifying if it were scripted for an insect horror movie.

“They’re aggressive,” he said, ending his uplifting talk, “but not poisonous.”

Armed with the information about the scorpion and how to treat its stings, Captain Sladek managed to return the SEAL to duty several days later. He was not the last to stay on our ward as a result of the wrath of the death stalker.

That night, I left the hospital late after dealing with a patient in crisis. The crisp night air of the desert spring had faded to a distant memory once summer had arrived, in April. The field between the hospital and the barracks, with its treacherous crevices and large rocks, was devoid of light. I stepped off the cracked sidewalk and reached into my blouse for my dog tags and the squeeze flashlight that hung with them.

At that moment, a loud whoosh in my ear caused me to duck instinctively; I lowered my head to my knees and placed my hands over my scalp. When I dared to look up, my eyes had adjusted to the pitch-black night. I focused on the field ahead of me.

They were vampire bats. At least fifty of them dove and swooped through the night air, tiny black fighter jets in a wild dogfight.

I watched them in disbelief and partial amusement. Of course there were bats here, I mused. And of course they were diving at my head while I walked to my barracks at night. Checking inside my boots every morning for potentially deadly scorpions was simply not enough.

The Eye in the Sky

My watch alarm beeped softly at 0420. I sat straight up and turned it off. I did not feel awake but slept so lightly most of the time that I never felt truly asleep either. In four minutes flat I stumbled out of my cot, added socks and tennis shoes to the olive green T-shirt and matching workout shorts I wore to sleep, brushed my teeth with bottled water, and navigated through the black passageways out the back door of my barracks. I stood in the darkness for a moment, looking for the signal from Bill in the distance: a flashing blue beam from his little squeeze flashlight.

He was there. I carefully moved over the uneven field that separated the men’s and women’s barracks, lighting the ground beneath my feet before I stepped. Together we traversed to the paved road and began the three-quarter-mile hike to the gym. That 0430 brisk walk was one of my favorite activities of the day. It was very quiet, relatively cool (low 100s), and we had yet to experience whatever humor or horror the day would bring.

With so many factors beyond our control in the deployment, cardiovascular workouts became a means to control one small piece of our lives. Depending on duty schedules and how much sleep we had had the night before, Bill, Karen, Katie, Jason, and I rotated who went each morning. Almost always, Bill and I remained the constant members of our insane early-morning workout club.

Watching the scarlet sun peek above the flat, brown horizon was a highlight of our ridiculous morning routine. Despite the chaos that might occur between the two, both sunrise and sunset in Iraq usually took our breath away with their beauty. That particular morning in late March, Bill and I watched the sunrise with new interest. As the ruby streaks spread across the sky and brightened the edge of our world, they silhouetted a strange object. We stared.

It was a giant blimp-shaped gray balloon. Tethered to the ground by a long rope, it hovered there, close to the headquarters buildings, simultaneously ominous and comforting. We had no idea what it was but figured it had to be important.

We came to call it the Eye in the Sky, because its duty, we learned, was to observe our base and the area surrounding it with sophisticated equipment that sent real-time signals to the Marines who needed to know these things. Of course, its true capability was secret and the source of only rumors for the likes of us, but what we did know was that the Eye in the Sky watched over us, day and night. Some speculated that the new surveillance came to us in the wake of the increased rocket attacks and casualties as the situation in Fallujah deteriorated. We did not care about the reason. We were happy to have it near.

The presence of the little dirigible led to loud, off-key group singing of the Alan Parsons Project song of the same name: “I am the Eye in the Sky, looking at you-oo-oo, I can read your mind . . .” This, of course, always caused fits of hysterical giggling.

Giggling was good. So the Eye in the Sky was good. And after it went up, the rocket attacks subsided for a few weeks. So the Eye in the Sky was great.

One morning a few weeks after the Eye appeared, Karen and I walked back from the gym together. It was 0610, and the April sun was warming up fast.

A very junior nurse corps officer, Karen had volunteered to come to Iraq. She told me she had joined the Navy specifically to take care of our Marines in combat and that she saw this deployment as a unique opportunity for the nursing experience of a lifetime. Her expectations had been met, and by April, she had made a career decision. Watching our nurse anesthetists in action, she knew her calling was to go on to graduate school and follow in their footsteps. Whether those footsteps would keep her in the Navy remained to be seen.

We chatted about our families, Karen telling me that her father was the fire chief in the New Jersey town where she’d grown up. Looking at her as she spoke, I suddenly sucked in my breath at the sight that unfolded in my peripheral vision.

A wall of sand was speeding toward us.

In the movie The Mummy, the sand rises up as a huge, angry face, chasing after the protagonists and threatening to swallow them whole as they race across the desert. It was like that, only without t

he gigantic gaping mouth. Karen noticed my expression and followed my gaze just in time to know she needed to turn her back — as I did — to the sand. We bent at our waists and scrunched our eyes shut. The sand struck us as we turned, a blast of pelting rocks and dirt in a gust of wind strong enough to knock us over if we had not been holding on to each other for support. It lasted five seconds and disappeared while our eyes were shut.

We stood up and looked at each other.

“Ow,” Karen said, gently touching the back of her leg. “I think a layer of my skin is gone.”

“Three of my best friends in the Navy are dermatologists now.” I smiled. “One of them, Mary, sent me a card joking that after my deployment I would have no need for microdermabrasion. I’ll have to tell her now I understand what she meant.”

Karen grinned, wincing a little.

That little burst of sand was a taste of things to come, as springtime in Iraq brought with it one of the most feared parts of deployment to the Middle East: the sandstorm.

In the weeks that followed, these periodic squalls of sand descended on our base in howling fits, like screaming trapped animals. Visibility was so poor I sometimes could not see my hand in front of my face. But unlike our short-lived dust-devil experience walking back from the gym, the actual storms lasted hours, or days. The sky turned brown, and then orange, and then red. Legend says that in some areas, it turns black. Thankfully, we never got past red.

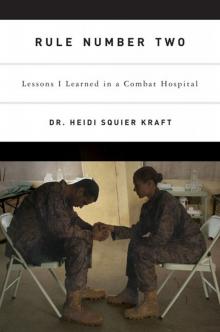

KAREN LOVECCHIO

All this gusting sand meant the Eye in the Sky had to come down, of course. If the wind got too strong, it might blow away.

One night in the middle of one of the sandstorms, I fell asleep with the pathetic cry of the wind rattling my window and whistling through the roof of our building. It had been a twelve-hour day of seeing patients, including being called back to the hospital in the evening to deal with a staff personality issue. Sometimes physical exhaustion trumps all external sensation. I turned on Norah Jones in my headphones and fell asleep in seconds.

Rule Number Two

Rule Number Two