- Home

- Heidi Squier Kraft

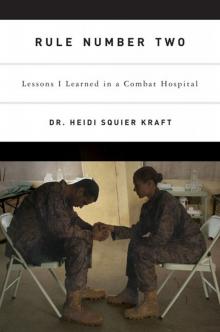

Rule Number Two Page 5

Rule Number Two Read online

Page 5

We heard the roar of the Black Hawk landing outside. The ICU team strapped Corporal Dunham to the gurney, and six litter bearers took its handles, a seventh lifting his IV bag. I kept holding his hand. Steve started hand-ventilating him then, and we all moved into the passageway. It seemed that every person in the company lined those walls as we walked through them and out the double doors. I gripped Dunham’s hand tightly and kept talking, unable to control the manic hope in my voice. I told him the doctors and nurses at his next stop would take good care of him, that we would never forget him, and that I was proud of him for fighting so hard. We walked all the way to the helicopter. The Army flight medic met us at the hatch. He motioned the litter bearers to the holding rack.

And then I had to let him go.

The litter team loaded him in the bird, and we all ducked under the vortex of the rotor blades and backed away. The Black Hawk took off. I stood paralyzed in the light brown dirt, watching the cloud of dust rise and the huge propeller lift them to the bright blue horizon. The Black Hawk was joined by an attack escort, and together they made a wide, circling turn over us and disappeared. I turned around. A large group of people had gathered around the back doors and stood in quiet awe. The rest of our patients were either in surgery or on the ward. We could stop for a moment.

I was suddenly aware of my body violently trembling at my knees. I raised shaky hands to my face without realizing I still had my gloves on. And then the tears came.

Combat Action Ribbon

“There are five thousand Marines at Al Taqqadum with no mental health support. I need you to take a psych tech and go down there. Assess the need, talk to the docs, and set up a system so these Marines are covered.”

“I see. And when do you need me to do this, sir?”

“Tonight. With me. Convoy leaves at 0200.”

The commanding officer of our medical battalion spun on the heel of his boot and strode away without waiting for my reply.

It was April. Fallujah was burning, and the Marines’ siege of the city was splashed across front pages around the world. Surgical companies and the smaller forward surgical units — like the one at Al Taqqadum (which we called TQ) — were overwhelmed with casualties. We were no exception.

I watched him walk away, incredulous that he had not been briefed on the fourteen injured patients our group had treated that day. And then I realized the truth. Someone had briefed him. Although it must have been clear to him for weeks that a mistake in medical planning made reassignment of psych resources necessary, the CO had decided to sum it up in a three-sentence order to me on the afternoon of our worst mass casualty to date.

The convoy would take us through Hit, a hostile town just south of our base. We had been informed by our Marines that fighting was ongoing in Hit, and there was a possibility of another wave of wounded Marines from the area within hours.

Adrenaline shot through my body, sending a prickly sensation to my toes and fingers. The windows in our concrete hospital structure rattled fiercely as a huge Marine transport helicopter hovered above us, waiting to land. The volume made communication without yelling impossible. I watched as Marines and Sailors formed litter teams and waited inside the glass doors for the signal to go.

The first group ducked their heads and ran to the bird. The noise intensified with the open hatch, so I got earplugs from the tiny pocket on my shoulder and stuffed them in my ears. Watching from the window, I saw the gurneys stacked high inside the helo. The adrenaline rush turned to anger.

I marched down the short hallway between the casualty receiving area and our company commander’s office and knocked loudly on her door. No more than five feet tall, the Navy laboratory officer in command of our company wore pink blush and lipstick nearly every day. It may have been the only trace of the color pink in all of Iraq.

At five-eight in my boots, I towered over her and had to look down to make eye contact. She looked up at me. I calmly asked her about the unnecessary risk of a convoy for Petty Officer Blythe and me in this clearly nonemergent situation. I reminded her that we expected numerous additional casualties today and that we were located on an air base. We could hitch a forty-five-minute helicopter hop to TQ twice a day any day of the week. She agreed to talk to the CO.

Less than one hour later, she sent for me and explained that the Marines would not take me on a convoy if they thought it was dangerous. To this day I think that may have been the most ridiculous statement I have ever heard.

I told Jason, Bill, and Steve about my convoy that night, certain that my eyes betrayed my anxiety. For most of our seven months at Al Asad, the four of us ate only breakfast and lunch in the chow hall. The walk was long, and the lines at dinner were longer. Despite this, the three men who would become my dear friends suggested we go to dinner together that night.

Bill and Steve were the physician assistants of our company. Both had been in the Navy for many years, rising to the rank of Navy Chief. They had both been independent-duty corpsmen, responsible for the health of Sailors in situations when physicians were not available. They teamed up with Jason early on as roommates, and their combined vast deployment experience led to important quality-of-life projects, from which I directly benefited. Like the decision early on that we would watch the entire series of The Sopranos, and we would make it last the whole deployment. It was something to look forward to; it mattered. They knew it.

Best of all, though, they made me laugh. Their experiences had given them the wisdom to see the humor in situations that might not have seemed funny at all to someone like me, who didn’t know better. We laughed a lot together.

And that night, together, we braved the crowds of thousands of hungry Marines and trudged the half mile to the warehouse turned chow hall. As we approached the two long lines leading to the entrance, Bill ran up to the front to check the menu. He walked back to us with a huge grin on his face. The “express” line boasted corn dogs that night. This was a wonderful surprise, as we had grown to truly love these corn dogs. We grinned at each other like delighted children in the lunch line.

Conversation was sparse during the meal. I knew my friends were angry at the CO and company commander for their collective decision. I knew they were concerned for my safety. Most of all, I knew they felt frustrated that they could not protect me that night.

After dinner, I proceeded to my room and shoved bare necessities into my Marine Corps–issued backpack, called an ALICE pack. Suddenly inspired, I wrote six letters. One of them was to Mike.

I want you to know that, nearly five years ago, you were my dream-come-true when I walked down that aisle and saw you up there in your dress blues. And then sixteen months ago, two more dreams-come-true entered our lives and looked up at us with big blue eyes. No matter what happens tonight or any night out here, my life is complete. I am a lucky woman. All my dreams have come true.

I addressed the cards, placed them in a neat stack on the edge of my cot, and returned to the guys’ barracks to watch a movie.

Jason lent me his cushioned stadium seat for the long Humvee ride. He said it had served him well in his deployment to Iraq with the Marines in 2003, and he hoped it would help make me slightly more comfortable. I smiled at him, touched by the gesture. All three of them hovered around me. I felt their worry intensely.

But no one knew what to say. So no one said a word.

Just after midnight, the movie long over, I sat on my cot alone, cleaning my weapon by the light of my headlamp. My fingers trembled, and the twisting sensation in my gut felt the same as it had during the first rocket attack. It was fear, of course, but that night I refused to name it.

Petty Officer Blythe knocked on my door at 0100, his ALICE pack over his shoulders. His blue eyes twinkled, and he smiled easily at me. Thankful for his company, I hoisted my pack, and without a word we walked out of my barracks and up the road to the staging area behind the hospital.

A twenty-five-vehicle convoy waited for us around the corner.

The CO met us, we exchanged pleasantries, and then he left to talk to higher-ranking people. His driver, a tall, lanky lance corporal with a Texas accent, helped us load our bags in the back of the Humvee. I noticed the canvas sides of our vehicle and mentally compared them to the armored plates on those in front of and behind us. I was opening my mouth to ask our driver about it when he swung the door of the vehicle open for me, wiggling its metal handle in demonstration.

“Here’s your hatch, ma’am,” the Marine said. “It’s kind of stuck, see? It doesn’t open from the inside, so you’ll have to wait for me to let you out.”

“You’re kidding, right?”

“No, ma’am.”

Before I could ask the next stupid question, a group of five men approached us.

“We heard there were medical people on the ride tonight.” We introduced ourselves all around. They were Navy reservists, paramedics in their civilian lives, and now hospital corpsmen who supported Marine convoys. The senior ranking man, a petty officer first class with a dark mustache and bright green eyes, described the situation.

“So, ma’am, here’s what’s going to happen when we get hit. If the incident occurs in front of you, your driver will move you to the right and we will come forward to care for casualties. We will meet you there and you both can help us out. If the incident is behind you, your driver will stop in place, and when he gives you the okay, if it’s safe, you can make your way back to us.”

He lost me with the first sentence.

“I beg your pardon. Did you say when we get hit?”

“Well, yeah — we’re going right through Hit and ending up only a few miles from Fallujah. It’s been pretty bad lately. Wouldn’t you say we’ve taken fire the last five out of six times?”

One of his colleagues nodded. “Sounds about right.”

“We have to expect it, ma’am. It’s the rule these days, not the exception.”

I stopped talking. Despite my increasing panic, I wanted desperately not to look like an idiot. I moved away from the conversation and looked up at the vast black night. Millions of flickering stars illuminated the dark canvas, horizon to horizon. While I struggled to slow my shallow breathing and meditate with words of prayer, a single star darted across the sky in a brilliant stream of light. I figured God was trying to tell me that we would be the exception that night. I made a wish.

Our Marine driver was leaning against the front of the vehicle, smoking a cigarette. He saw me and smiled. I managed a weak smile in return and walked over to him.

“Don’t worry, ma’am,” he said. “I’ll take good care of you.”

“Oh, I know you will,” I replied. That was the truth.

He dropped his cigarette and crushed it under his boot. “It’s pretty straightforward, ma’am. Just watch me the whole time. If we have to stop the vehicle, I want you to point your weapon out the window, square your chest with the door, and keep your eyes on me. I’ll get out of the vehicle — you don’t have to watch anything except me. If I shoot at something, I want you to empty your magazine in the same direction and then hit the deck of the vehicle. Okay?”

“Okay, but if I’m going to end up hitting the deck anyway, why empty my magazine? Why not go to the deck immediately?”

He grinned. “You have to fire your weapon, ma’am, in order to get the Combat Action Ribbon.”

“I don’t want the Combat Action Ribbon, Lance Corporal.”

“Sure you do.”

“No, I don’t. Read my lips. Medical. I don’t shoot this thing except when they make me practice at the range. Trust me on this.”

“But that’s why you want the CAR, ma’am. Imagine how awesome it would be for someone like you to have it.”

Someone like me. That made me smile.

“Thanks, but no thanks.”

“Believe me, if we go through this thing tonight, you’ll want it.”

I stopped arguing. He might have a point there.

The engines of the convoy grumbled to life. Marines and Sailors fastened helmet chinstraps, shouted last-minute orders, and mounted their vehicles. My friend the lance corporal opened my canvas door for me and smiled. I hoped he did not notice my trembling knees as I stepped forward. I climbed in, closed my eyes, and silently changed my prayer.

Dear God, please don’t let me shoot myself or any of the Marines on this convoy tonight. I opened my eyes and slid a round into the chamber.

Convoy

Our long string of desert tan vehicles crawled from the convoy staging area toward the front gate, stopping adjacent to a large, empty field.

The Marines dismounted. Aiming into the darkness, they tested first the big guns and grenade launchers mounted atop the larger trucks, then proceeded in descending order of size. I stood at the edge of the road and watched.

Despite my earplugs, the volume of the huge guns rattled my brain in its skull. My teeth and eyes ached even before hundreds of Marines holding M16 rifles stepped up to the barbed wire and someone yelled, “Fire!” Between spattering bursts of rifle fire, I felt increasingly alarmed at the thought of a headache on the convoy. Earlier unease had led me to dehydrate myself on purpose prior to the trip. I knew I would feel cold, uncomfortable, and possibly terrified on this little drive. That knowledge was anxiety provoking enough without the added worry that I might also need to go to the bathroom during those six hours.

A deep voice called for M9s. Everyone carrying a pistol moved to the edge of the field, including me.

I pointed my weapon at the top of one of the tiny hills and, on cue, fired a single shot into the darkness. The Marines and Sailors around me continued firing. I lowered my arm and clicked the safety on. One was enough.

“Load up!” a voice boomed. We did.

Our driver opened my canvas hatch, waited for me to arrange myself on Jason’s stadium chair, and slammed it behind me. We made brief eye contact, and he smiled.

The headlights of every vehicle were turned off. I sat motionless against my steel seat, the chill of the dropping temperatures creeping through me. Several minutes passed in the darkness before, one by one, engines turned over. Our driver donned night-vision goggles, or NVGs, and spent a few minutes making adjustments. Relief washed over me as I recalled fond memories of flying in the backseat of the Hornet using NVGs.* They brought the blackest of nights to surreal green life. I murmured a prayer of thanksgiving for superior technology.

The Humvee, it turns out, is built for many things. Passenger safety as we know it is not one; there were no seat belts to be found. Passenger comfort must have been even lower on the list of priorities. As the vehicle hit the first pothole of the night and my teeth slammed together, I realized that Jason’s foam cushion would function as the most basic of shock absorbers.

Resting on my thigh, my pistol vibrated with the undulations of the road. We moved through the front gate, one at a time, until the entire convoy was outside the wire.

My grip tightened.

Our vehicles picked up speed in unison. Leaning to my right, I peered over my driver’s shoulder. Even driving sixty-five miles per hour, he still maintained that perfect interval between vehicles. I smiled as I replayed our conversation about the Combat Action Ribbon. For Marines, I thought, earning that ribbon was a source of genuine pride, almost a definition of the values for which they stand. Psychologists who care for Marines, especially in combat, needed to comprehend that fact. It helped make sense of many things. My thoughts wandered to my husband, Mike, and I remembered the first time I saw him in his Charlies, the Marine Corps uniform equivalent of a business suit. He was a striking figure at six-four, with massive biceps and gold wings on his chest. My eyes drifted shut.

I finally understand, I thought, speaking to him in the dark.

We sped into the night. An ebony sky extended in every direction, and with each passing mile, new stars appeared. Starlight alone illuminated the road. Shuddering in the cold, I pulled my fleece face cover over my mouth and nose. I briefly considered

gloves but decided against them when I imagined how slippery the wool would feel next to my pistol. Slippery was not good.

After the first half hour, I allowed myself to lean my head back, focusing on the muscles in my shoulders, which felt like rubber bands under tension. Had it only been twelve hours since that mass casualty?

I scrunched my eyes shut, willing the tears to stay inside. Distracted by my trepidation about this convoy, I had not allowed myself time to think about Corporal Dunham. Or about that young lance corporal I had met early in the day as he recovered from surgery on our ward. I remembered the tattoos on his arms. One said USMC. And one, he told me, used to say SEMPER FI. After that day’s car bomb had taken out most of his forearm, only the S and the E remained.

I remembered his tears and the way he swiped mercilessly at them. He felt fear. He felt shame that far outweighed the fear. He went on to explain that he had been in Iraq almost two months. This injury would earn him his third Purple Heart. He told me he was afraid his luck was about to run out.

He was ashamed to feel afraid.

I remembered struggling to form the words that would normalize this nineteen-year-old man’s experience. And, using a therapeutic technique I made up as I went along, I consciously decided to take another path instead. I told him there was nothing normal about three Purple Hearts in two months. I told him there were no feelings that were usual for people in that situation. I told him he was going home. He laid his head on his pillow and sobbed without making a sound. I sat with him a long time.

I thought of my Brian, only seventeen months old. I pictured myself lying in bed when the phone rang in the darkness. I physically experienced that sick, sinking sensation that must invade every mother’s heart the moment she hears a shrill ring fracture the night. I thought of that lance corporal’s mother. I thought of Corporal Dunham’s mother. I bit my lip hard and tasted blood.

Rule Number Two

Rule Number Two